Only Connect

Jaya described to us her film. Dances of the Seasons, she explained, uses the Indian classical dance form, Bharatanatyaman, to demand respect for the earth. The film depicts a dancer who acts out the seasons of the epic Sanskrit poem Ritu Samhara. She wears a joyful smile as she celebrates the abundance and transformative power of nature, but in the last clip that Jaya showed us the smile is gone. Her environment has become so polluted that it is impossible for her any longer to make any meaningful connection with what is around her.

I was still thinking about this beautiful, sad film when the bus from the university dropped me off outside King Henry VIII School, only a short walk from Coventry railway station. I had more than an hour to kill before returning to London. It was obvious how I should spend that time: only connect.

I had never been to Coventry before. Just about the only thing I knew about the city was that its medieval cathedral had been destroyed during the Blitz and a new cathedral built in its place. So I would try to find it.

As I made my way across the ring road towards the city centre, not knowing how best to navigate the heavy traffic of the evening rush hour, the invisible tug of a neglected old film pulled me along. Humphrey Jennings made The Heart of Britain in the winter of 1940 in response to the city’s destruction. Produced at a time when the country was not yet entirely confident of its future survival, the immediate purpose of the film was to win sympathy and support for British cities that were still under nightly attack.

All of a sudden, ahead of me, I saw the shell of the old cathedral. Through the arch of a medieval window, I had a glimpse of Magritte-like clouds where a roof would once have been, rekindling the impact of a film that I hadn’t seen in thirty years.

In one extraordinary sequence, The Heart of Britain pays a startlingly humanist tribute to “the genius of the Germany that once was”. Jennings shows an orchestra in Manchester playing Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, but then, in ironic counterpoint, splits sound and picture to set the continuing music against the blitzed buildings of Coventry. As one city in the heart of Britain expresses solidarity with another – Jennings’ camera-eye panning across the line of ruins like the notes on a score – Beethoven’s music has the effect of exposing the moral corruption of a once great nation.

Anchoring the poetry of the film is the human warmth of Mrs Hyde, the head of the Coventry branch of the Women’s Voluntary Service. She describes what it was like to help with the rescue efforts: “You know, you feel such fools standing there in a crater, pitch darkness of night, and pouring mugs of tea to the men bringing out bodies. You feel useless, until you know that there’s someone there, actually in that bombed house who’s alive, and who you can give that tea to. And then to hear the praises of the men themselves: “That tea is jolly good. I’ve just washed the blood and dust out of my mouth.” And we feel that we really have done a job. And a useful job.”

A model of good humour, resolve, civic duty and fellow feeling, 85 years later Mrs Hyde remains relevant to what as a society I hope we would still wish to be. That evening, 28 March 2025, as I walked around the 1940 ruins of the old cathedral, I was scrolling on my phone through the headlines about an earthquake that had struck Myanmar earlier that day, but I could as easily have been reading about the latest examples of “man’s inhumanity to man” in Ukraine, Palestine or Sudan, which it is up to the other Mrs Hydes to tackle.

On 14 November 1940, about 500 German bombers flew over Coventry. In that one night over 4,000 homes were flattened and nearly 600 people killed. It was an early lesson in how to destroy a city. But the lessons that followed – Cologne, Dresden, Hiroshima – were so appalling that over the next 85 years we hoped against hope that mankind had learned to dispense with such violence. But then, and then, and then…

Soon after the destruction of Coventry’s cathedral two charred medieval roof timbers were found on the ground in the shape of a Cross. Bound together, they were set up on an altar that had been built out of the rubble. On the wall behind were painted in large letters the words: FATHER FORGIVE.

I tried to photograph the words with my phone, because they seemed relevant too, but I lost the necessary focus in the magnification required to reach the wall. But whether in colour or black-and-white, the place was eerily the same as it had been in September 1941 when the mayor of Coventry, Alderman John Moseley, gave Churchill a tour of the ruins. During this visit, the prime minister, moved by what he had seen, promised that the nation as a whole would bear the expense of rebuilding the city.

“Only connect.” It was this idea that was a key to Jaya’s film as well as Jennings’ films. It was this idea, too, that inspired the design of the modern cathedral. Joining with the ruins of the old, the new building was both a symbol of unity and a permanent reminder of the folly of war.

In 1962, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, gave the sermon when the cathedral was consecrated: “It went down in flames, it rises today in new glory,” he said. “Here, too, is a house which speaks of peace, of reconciliation: nations which have been divided see in it a sign that God can make men brothers.”

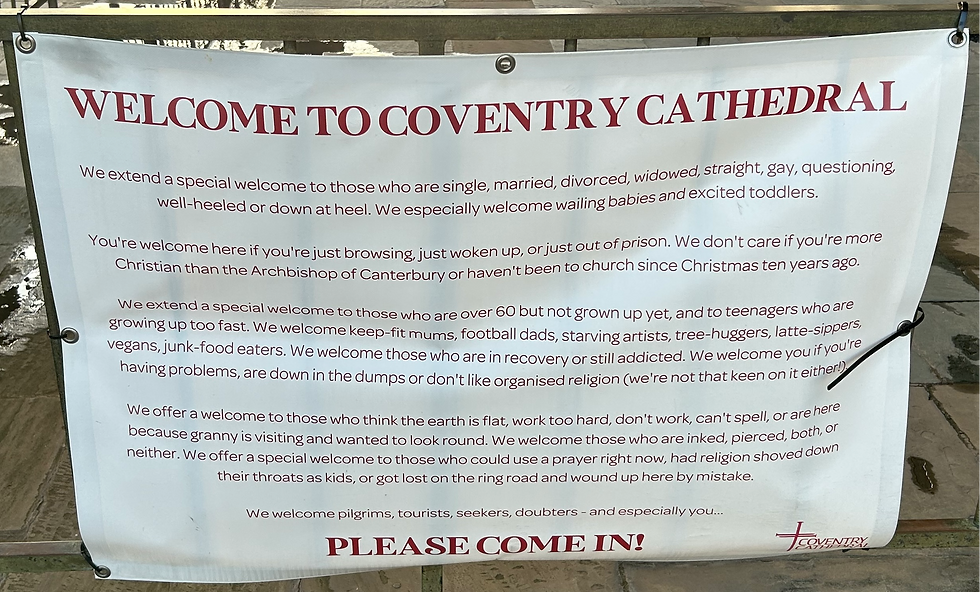

I was pleased to find outside the cathedral a welcome note, which suggests that the spirit in which it was consecrated remains robustly alive today.

I had to rush back to the station to catch my train. But on the London-bound platform, I had a few moments to learn some more about the City of the Three Spires. Mrs Hyde would become its mayor for a year in 1957. She was among the congregation when the new cathedral was consecrated. But in the following year, 1963, she was killed in a car accident while on holiday in Scotland. Chance and fate: you must do what you can while you can.

Coventry Station tells the story of its city well. The poet Philip Larkin, an old boy of King Henry VIII School, is remembered on a good, solid plate of steel, but the most affecting display I saw was about an amateur photographer called William Bawden, whose teenage son Percy had died as Coventry was recovering from the devastation of the Great War. “As he came to terms with death and disaster, Bawden walked and photographed,” the exhibit label explained, “exploring the familiar and trusted places and spaces of Coventry.”

At this point the train for London pulled into the station. There was just enough time for me quickly to take one last photograph – of a photograph: Bawden’s picture of the city’s timeless cathedral, still intact as it had been for nearly 500 years.

Comments